Iraqi Detainees: Ordinary People, Extraordinary Ordeals

Chris Bartlett | Jordan, Turkey

Photographer: Chris Bartlett

Exhibit Title: Iraqi Detainees: Ordinary People, Extraordinary Ordeals

Location: Jordan, Turkey

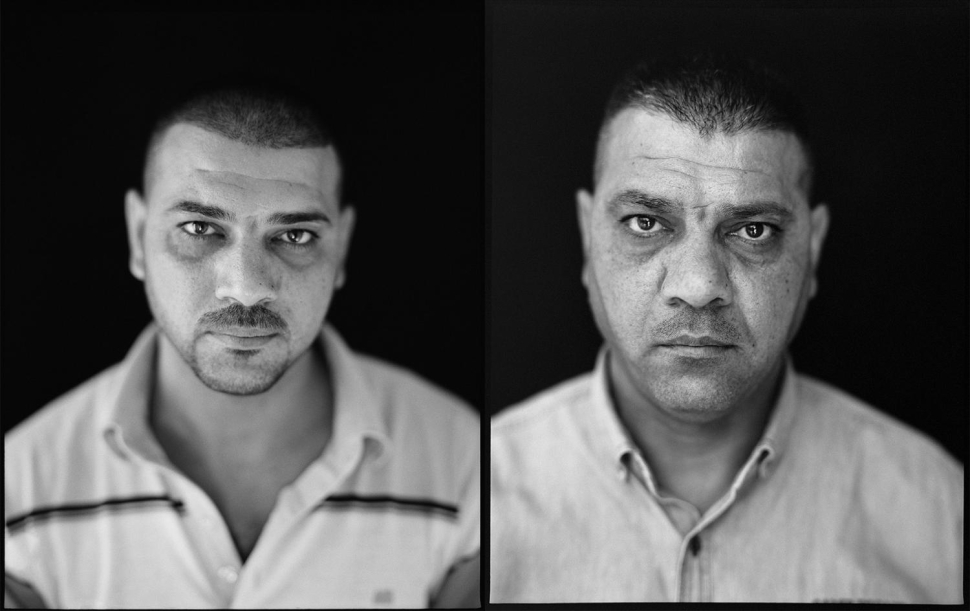

This is a self-funded portrait project of ordinary and innocent Iraqis who were detained and tortured by the Americans and their military subcontractors in the early years of the Iraq war. The portraits were made in Amman, Jordan and Istanbul, Turkey in 2006 and 2007. In 2019 I crowdfunded a followup. I found 4 of the earlier subjects and brought them to Istanbul for updated portraits and interviews.

This is a self-funded portrait project of ordinary and innocent Iraqis who were detained, tortured, and abused by the U.S. military and their subcontractors after the United States’ invasion of Iraq. In the first few years of the conflict, which began 20 years ago this March, tens of thousands of individuals were detained by the coalition forces. Most of those detained were innocent and it is not an exaggeration to say that the vast majority of Iraqis picked up were harassed, mistreated, abused, or tortured in some way. How you describe their treatment derives in part from how you define torture. Is it, as the government defined it, only torture when it leads to “death, organ failure, or permanent damage”? Is waterboarding torture? Is “Enhanced Interrogation” different than torture? If one is stripped naked, chained to a door, locked in a darkened room for 23 hours a day, beaten at regular intervals, threatened with dogs for weeks or months on end with one bathroom break and one meal a day – is that considered torture? Our government didn’t define it as so. If your son or daughter happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time while traveling abroad, and they were picked up and treated this way, with no charges filed and no notice to family given, would you feel that they had been tortured? If the country that they were visiting was on high terror alert would it justify that treatment? The individuals shown in these portraits are Iraqis who were detained under the auspices of the United States military and its surrogates. All were tortured and abused for months into years and all were released without charges and often without explanation. The portraits were taken in the spring of 2006 in Amman, Jordan and the summer of 2007 in Istanbul, Turkey.

The issue of abuse came to light with the discovery of the soldiers’ private photo sharing of the graphic interrogation pictures with their “point and shoot” digital cameras. And while the discovery of the photos brought widespread awareness of the injustice, the imagery also further dehumanized the victims. The camera had become an instrument of torture and with few exceptions the only images the world had seen of the victims were those taken by the victimizers.

I was invited to participate by the lawyer Susan Burke, who at the time, was the lead attorney representing the Iraqis in class action lawsuits against the military subcontractors. (The military cannot be sued directly.) There is still one case working through the courts: Al Shimari, et al. v. CACI that was filed in June, 2008 by the Center For Constitutional Rights. The project was shown at the Open Society Foundations’ Moving Walls exhibition in 2008. In 2014 it was reinterpreted as a container installation for Photoville in NYC. It subsequently went to Houston Fotofest, and the Hamburg Triennial. The project was covered by the BBC, NPR, Canadian Public Radio, Al Jazeera among others.

In 2019, 15 years after the detainee abuse came to light, I crowd-funded a followup. I found 4 of the subjects from 2006-7 and arranged for them to come to Istanbul. I made updated portraits and recorded video interviews. The takeaway of that experience was that the pain, anxiety, and trauma felt by the victims was as acute in 2019 as it was when they were released 15 years earlier. This is where this project crosses into the larger issue of the legacy of trauma. This followup chapter has yet to be exhibited.

As we enter 2023 it is nearly 20 years since the detainee abuse was first reported. Most Americans are not aware of the extent of the practice of torture in the early years of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. It was designed, planned and implemented from the highest levels of our government. The techniques were researched, recorded, and became routine for detainee treatment. The Americans’ use of torture harmed our global standing as a proponent of human rights and became a recruiting message for ISIS and Al-Qaeda. Torture seeped into our national consciousness and was further normalized through popular culture: the show 24 and the film Zero Dark Thirty being two of the most prominent examples. My goal from the outset has been for Americans to see the faces of the innocent victims of this abuse and for future leaders to understand the moral and geopolitical ramifications of the choice to torture. If there ever was such a thing as American exceptionalism, it ended here.

Make Comment/View Comments